Feuillets Jack Newman

Jaunisse - ictère

Feuillets Jack Newman

Version 2005 ; version anglaise 2009 ici, en bas de page

Introduction

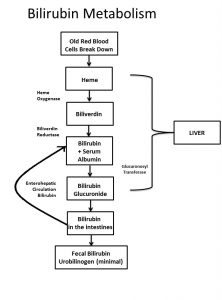

La jaunisse est causée par l'accumulation dans le sang de la bilirubine, un pigment jaune provenant de la destruction des globules rouges. La destruction des globules rouges est un processus normal, et la bilirubine libérée ne cause habituellement pas d'ictère car le foie la métabolise, et elle est ensuite éliminée dans les selles. La jaunisse est toutefois fréquente chez le nouveau-né car le foie, qui fabrique les enzymes métabolisant la bilirubine, est relativement immature. De plus, les globules rouges sont plus nombreux chez les nouveau-nés que chez les adultes; à la naissance, ils seront détruits en quantité importante. Si le bébé est prématuré, stressé par une naissance difficile, s'il y a destruction d'un nombre de globules rouges supérieur à la normale (comme cela se produit en cas d'incompatibilité sanguine), ou si sa mère est diabétique, le taux de bilirubine dans le sang sera plus élevé que ce qui est habituellement constaté.

Deux types de jaunisse

Le foie métabolise la bilirubine pour qu'elle puisse être éliminée (la bilirubine ainsi modifiée est appelée conjuguée, directe ou hydrosoluble, les trois termes ayant essentiellement la même signification). Cependant, si le foie fonctionne mal, notamment à cause de certaines infections, ou en cas d'obstruction des canaux biliaires, la bilirubine modifiée peut s'accumuler dans le sang et provoquer une jaunisse. Lorsque cela se produit, la bilirubine conjuguée est éliminée dans les urines qui deviennent foncées. Ces urines brunes sont le signe patent d'une jaunisse qui n'est pas « ordinaire ». La jaunisse dûe à la bilirubine conjuguée est toujours anormale, fréquemment grave, et elle doit faire l'objet d'un examen immédiat et approfondi. Sauf pour de rarissimes cas de maladies métaboliques, l'allaitement peut et doit continuer.

L'accumulation de bilirubine avant sa métabolisation hépatique peut être normale; c'est la jaunisse physiologique (cette bilirubine est appelée non conjuguée, indirecte ou liposoluble). Elle commence autour du 2ème jour, culmine au 3ème ou 4ème jour puis diminue et disparaît. Cependant, il existe certaines conditions qui peuvent aggraver ce type de jaunisse. Étant donné qu’il n’y a aucune association avec l’allaitement, il faut le poursuivre. Si, par exemple, le bébé a une jaunisse grave causée par une destruction trop rapide des globules rouges, ce n'est pas une raison pour interrompre l'allaitement. Il faut le continuer.

La soi-disant jaunisse au lait maternel

Il existe un type de jaunisse appelée «jaunisse au lait maternel». Personne n'en connaît la cause. Pour poser ce diagnostic, il faut que le bébé soit âgé d'au moins une semaine. Il est intéressant de mentionner que nombre de bébés ayant ce type de jaunisse ont aussi eu une jaunisse physiologique, parfois plus importante que la normale. Le bébé exclusivement allaité devrait avoir une prise de poids satisfaisante, plusieurs selles quotidiennes, des urines claires et abondantes, et être dans l'ensemble en bonne santé (voir article n° 4, Mon bébé prend-il assez de lait?). Dans un tel cas, le bébé peut avoir ce que certaines appellent une jaunisse au lait maternel, bien que des infections urinaires, un dysfonctionnement thyroïdien, ou quelques maladies rares peuvent aussi induire un tableau clinique similaire. La jaunisse au lait maternel est à son maximum entre le 10ème et le 21ème jour, et peut durer deux à trois mois.

La jaunisse au lait maternel est normale. Il est rarement nécessaire d'arrêter l'allaitement, même temporairement. Un traitement, comme la photothérapie, ne s’avère nécessaire que très occasionnellement. Rien ne prouve que ce type de jaunisse puisse causer un quelconque problème au bébé. Il ne faut pas interrompre l'allaitement sous prétexte «d'établir un diagnostic». Si le bébé exclusivement allaité se porte bien, aucune raison, aucune, ne justifie la suspension de l'allaitement ou la supplémentation avec un dispositif d'aide à l'allaitement. L'idée que quelque chose ne va pas chez les bébés souffrant de jaunisse provient du fait que l'on compare les bébés allaités aux bébés nourris au lait industriel, et que ce qui est constaté chez ces derniers est considéré comme la norme à laquelle les bébés allaités doivent se conformer. Cette manière de penser, presque universellement répandue parmi les professionnels de la santé, va à l'encontre de la logique même. Il est vrai que les bébés nourris au lait industriel présentent rarement une jaunisse après la première semaine de vie; lorsque c'est le cas, il y a généralement un problème médical. On s'inquiète donc pour les bébés ayant une jaunisse au lait maternel, et on tient à « faire quelque chose ». Pourtant, selon notre expérience, la plupart des bébés exclusivement allaités qui sont en parfaite santé et dont la prise de poids est bonne présentent encore des signes de jaunisse à cinq ou six semaines post-partum, voire même plus tard. En fait, la question devrait être: « Est-il normal de ne pas constater de jaunisse, et devrait-on s'inquiéter en l’absence de jaunisse? » Ne cessez pas l’allaitement à cause d'une jaunisse « au lait maternel ».

La jaunisse chez le bébé qui ne reçoit pas assez de lait maternel

Des taux de bilirubine supérieurs à la normale ou une jaunisse prolongée peuvent survenir si le bébé ne reçoit pas suffisamment de lait. Une « montée de lait » tardive, des routines hospitalières qui limitent l'allaitement, ou, plus souvent encore, une mauvaise prise du sein par l'enfant, peuvent avoir pour conséquence une absorption insuffisante de lait par le bébé (voir l’article n° 4, Mon bébé prend-il assez de lait?). Lorsque le bébé reçoit peu de lait, ses selles deviennent rares et peu abondantes, ce qui provoque la réabsorption dans le sang de la bilirubine présente dans le tube digestif du bébé, étant donné que l’élimination par les selles est limitée. Évidemment, la meilleure façon d'éviter la jaunisse causée par une absorption insuffisante de lait est un bon démarrage de l'allaitement (voir article n° 1, L’allaitement maternel : un bon départ). La solution pour ce type de jaunisse n'est certainement pas de cesser l'allaitement ou encore donner des biberons. Voir le Protocole pour augmenter l’ingestion de lait maternel par le bébé. Si le bébé tète correctement, des tétées plus fréquentes peuvent suffire à faire baisser plus rapidement le taux de bilirubine, quoique, en réalité, il n’est pas nécessaire d’intervenir. Par contre, si le bébé tète mal, une correction de la mise au sein lui permettra de téter plus efficacement et de recevoir davantage de lait. La compression du sein peut aussi être utile pour aider le bébé à obtenir plus de lait (voir l’article n° 15, La compression du sein). Si l'amélioration de la mise au sein et la compression du sein ne règlent pas le problème, il serait approprié d’utiliser un dispositif d'aide à l'allaitement pour la supplémentation (voir l’article n° 5, Utilisation d'un DAL).

Voir aussi le Protocole pour augmenter l’absorption de lait maternel. Visionnez les vidéos démontrant la prise du sein, comment reconnaître que le bébé boit au sein, et la compression du sein.

La photothérapie

La photothérapie augmente les besoins liquidiens du bébé. Si le bébé tète bien, des tétées plus fréquentes suffiront à satisfaire ces besoins accrus. Cependant, s'il semble nécessaire de donner au bébé des liquides supplémentaires, il est préférable d'utiliser un dispositif d'aide à l'allaitement contenant du lait maternel exprimé, du lait exprimé sucré ou de l’eau sucrée, plutôt que de donner des compléments de lait industriel.

Questions? (416) 813-5757 (option 3) ou drjacknewman@sympatico.ca ou mon livre Dr. Jack Newman’s Guide to Breastfeeding Traduction de l’article n°7, « Breastfeeding and jaundice » Révisé en janvier 2005. Dr Jack Newman, MD, FRCPC

© 2005 Version française, février 2005 par Stéphanie Dupras, IBCLC, RLC Peut être copié et diffusé sans autre autorisation, à condition qu’il ne soit utilisé dans aucun contexte où le Code international de commercialisation des substituts du lait maternel de l’OMS est violé.

Version anglaise révisée juillet 2009 juin 2017

Breastfeeding and Jaundice

Jaundice is due to a buildup in the blood of bilirubin, a yellow pigment that comes from the breakdown of old red blood cells. It is normal for old red blood cells to break down, but the bilirubin formed does not usually cause jaundice because the liver metabolizes it and gets rid of it into the gut. The newborn baby, however, often becomes jaundiced during the first few days because the liver enzyme that metabolizes bilirubin is relatively immature. Furthermore, newborn babies have more red blood cells than adults, and thus more are breaking down at any one time; as well many of these cells are different from adult red cells and they don’t live as long. All of this means more bilirubin will be made in the newborn baby’s body. If the baby is premature, or stressed from a difficult birth, or the infant of a diabetic birth parent, or more than the usual number of red blood cells are breaking down (as can happen in blood incompatibility), the level of bilirubin in the blood may rise higher than usual levels. See also our blog Breastfeeding, Bilirubin and Jaundice

How bilirubin is formed from dying red blood cells

It should be emphasized that bilirubin has an undeserved bad reputation. It is an innocent bystander that is blamed for brain damage when in fact, the problem is not the bilirubin. It is the set of circumstances that allowed the bilirubin to enter the brain that is the real problem. Severe lack of oxygen when the baby is asphyxiated or severe anemia due to very rapid breakdown of red blood cells, Rh incompatibility or ABO incompatibility, which is also associated with metabolic disturbances causes the damage that allows bilirubin to enter the brain and made physicians believe that the bilirubin was the problem. In fact, bilirubin is an antioxidant and actually protects the baby from damage.

The most common cause of higher than average bilirubin levels in the first few days of life is not breastmilk, but rather the fact that the baby is not breastfeeding well and not getting adequate amounts of breastmilk. Though giving formula works to bring down the bilirubin, giving formula, especially by bottle, interferes with breastfeeding as bottles teach the baby a poor latch, which then cause the breastfeeding parent sore nipples and/or result in the baby not getting enough milk from the breast. The answer is for the breastfeeding parent to get good help with breastfeeding and only if the baby still does not get adequate amounts of milk from the breast, then supplementation should be considered and given by lactation aid at the breast.

For even more information about jaundice, click here.

TWO TYPES OF JAUNDICE

The liver changes bilirubin so that it can be eliminated from the body (the changed bilirubin is now called conjugated, direct reacting, or water soluble bilirubin–all three terms mean essentially the same thing). If, however, the liver is functioning poorly, as occurs during some infections, or the tubes that transport the bilirubin to the gut are blocked, this changed bilirubin may accumulate in the blood and also cause jaundice. When this occurs, the changed bilirubin appears in the urine and turns the urine brown or brownish. This brown urine is an important clue that the jaundice is not “ordinary”. Jaundice due to conjugated bilirubin is always abnormal, frequently serious and even life-threatening, and needs to be investigated thoroughly and immediately. Except in the case of a few extremely rare metabolic diseases, breastfeeding can and should continue.

Accumulation of bilirubin before it has been changed by the enzyme of the liver may be normal— “physiologic jaundice” (this bilirubin is called unconjugated, indirect reacting or fat soluble bilirubin). Physiologic jaundice begins about the second day of the baby’s life, peaks on the third or fourth day and then begins to disappear. However, there may be other conditions that may require treatment that can cause an exaggeration of this type of jaundice. Because these conditions have no association with breastfeeding, breastfeeding should continue. If, for example, the baby has severe jaundice due to rapid breakdown of red blood cells, this is not a reason to take the baby off the breast. Breastfeeding should continue in such a circumstance.

SO-CALLED BREASTMILK JAUNDICE

There is a condition commonly called breastmilk jaundice. No one knows what the cause of breastmilk jaundice is. In order to make this diagnosis, the baby should be at least a week old, though interestingly, many of the babies with breastmilk jaundice also have had exaggerated physiologic jaundice. The baby should be gaining well, with breastfeeding alone, having lots of bowel movements, passing plentiful, clear urine and be generally well (see the information sheet “Is my Baby Getting Enough Milk?”and our video clips showing how to tell if the baby is drinking well). In such a setting, the baby has what some call breastmilk jaundice, though, on occasion, infections of the urine or an under functioning of the baby’s thyroid gland, as well as a few other even rarer illnesses may cause the same picture. Breastmilk jaundice peaks at 10-21 days, but may last for two or three months. Breastmilk jaundice is normal. Rarely, if ever, does breastfeeding need to be discontinued even for a short time. Only very occasionally is any treatment, such as phototherapy, necessary. Yes, interrupting breastfeeding for a day or two will bring down the bilirubin, but a day or two of bottle feeding may result in breastfeeding becoming very difficult. Some babies have refused to latch on after 24 to 48 hours of bottle feeding.

There is not one bit of evidence that this jaundice causes any problem at all for the baby. Breastfeeding should not be discontinued “in order to make a diagnosis”. If the baby is truly doing well on breast only, there is no reason, none, to stop breastfeeding or supplement even if the supplementation is given with a lactation aid, for that matter. The notion that there is something wrong with the baby being jaundiced comes from the fact that the formula feeding baby is the model we think is the one that describes normal infant feeding and we impose it on the breastfed baby. This manner of thinking, almost universal amongst health professionals, truly turns logic upside down. Thus, the formula feeding baby is rarely jaundiced after the first week of life, and when he is, there is often something wrong. Therefore, the baby with so called breastmilk jaundice is a concern and “something must be done”. However, in our experience, most exclusively breastfed babies who are perfectly healthy and gaining weight well are still jaundiced at five to six weeks of life and even later. The question, in fact, should be whether or not it is normal not to be jaundiced and is this absence of jaundice something we should worry about?

Do not stop breastfeeding for “breastmilk” jaundice. “Breastmilk jaundice” does not need to be treated. It is normal!

NOT-ENOUGH-BREASTMILK JAUNDICE

Higher than usual levels of bilirubin or longer than usual jaundice may occur because the baby is not getting enough milk. This may be due to the fact that the breastfeeding parent’s milk takes longer than average to “come in” (but if the baby feeds well in the first few days this should not be a problem), or because hospital routines limit breastfeeding or because, most likely, the baby is poorly latched on and thus not getting the milk which is available (see the information sheet “Is my Baby Getting Enough Milk?” and our video clips showing how to tell if the baby is drinking well). When the baby is getting little milk, bowel movements tend to be scanty and infrequent so that the bilirubin that was in the baby’s gut gets reabsorbed into the blood instead of leaving the body with the bowel movements. Obviously, the best way to avoid “not-enough-breastmilk jaundice” is to get breastfeeding started properly (see the information sheet “Breastfeeding—Starting Out Right”). Definitely, however, the first approach to not-enough-breastmilk jaundice is not to take the baby off the breast or to give bottles. If the baby is breastfeeding well, more frequent feedings may be enough to bring the bilirubin down more quickly, though, in fact, nothing really needs be done. If the baby is breastfeeding poorly, helping the baby latch on better may allow him to breastfeed more effectively and thus receive more milk. Compressing the breast to get more milk into the baby may help (see the information sheets “Latching and Feeding Management” and “Breast Compression”). If latching and breast compression alone do not work, a lactation aid would be appropriate to supplement feedings (see the information sheet “Lactation Aid”). See also the information sheet “Protocol to Increase Breastmilk Intake” and our video clips for help with latching, how to know the baby is getting milk, how to use compressions, as well as other information.

PHOTOTHERAPY (BILIRUBIN LIGHTS)

Phototherapy increases the fluid requirements of the baby. If the baby is breastfeeding well, more frequent feeding can usually make up this increased requirement. However, if it is felt that the baby needs more fluids, use a lactation aid to supplement, preferably expressed breastmilk, expressed milk with sugar water or sugar water alone rather than formula.

The information presented here is general and not a substitute for personalized treatment from an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) or other qualified medical professionals.

This information sheet may be copied and distributed without further permission on the condition that you credit International Breastfeeding Centre and it is not used in any context that violates the WHO International Code on the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (1981) and subsequent World Health Assembly resolutions. If you don’t know what this means, please email us to ask!

©IBC, updated July 2009, June 2017